Modern energy systems demand more than just power delivery. As distributed assets and volatile demand patterns become the norm, smart grids emerge as the foundational architecture enabling flexibility, visibility and control. For energy professionals tasked with optimizing performance, ensuring reliability and aligning with market signals, smart grids are no longer optional. They are essential.

From Traditional Grids to Smart Infrastructure

Limitations of Legacy Grid Systems

Conventional power grids were designed for one-way electricity flow, from large, centralized plants to passive consumers. These systems struggle to accommodate bidirectional flows, real-time pricing signals and the increasing presence of variable renewables. Lack of granular visibility and delayed response times often result in inefficiencies, unnecessary curtailment and growing reliability risks.

Core Components of a Smart Grid

Smart grids are not a single technology but a layered integration of digital infrastructure. Key components include:

- Advanced Metering Infrastructure (AMI) for real-time consumption data

- Supervisory Control and Data Acquisition (SCADA) systems for substation and feeder automation

- IoT-based sensors and edge controllers for distributed visibility

- Secure communication networks to ensure seamless coordination across grid nodes

Together, these elements transform a static grid into an adaptive, intelligent platform.

Real-Time Monitoring and Control Capabilities

Advanced Metering Infrastructure (AMI)

AMI extends visibility to the edge of the grid. With high-frequency data from smart meters, operators can identify consumption trends, detect anomalies and offer dynamic pricing based on real-time conditions. For consumers, this opens the door to demand-side participation and time-sensitive energy decisions.

Grid Automation and Sensing Technologies

Grid automation technologies, such as remote fault isolation and feeder switching, drastically reduce outage durations and improve restoration times. Sensors placed along feeders and substations continuously monitor voltage, load and frequency parameters, enabling preemptive action rather than reactive fixes.

Integrating Distributed Energy Resources (DERs)

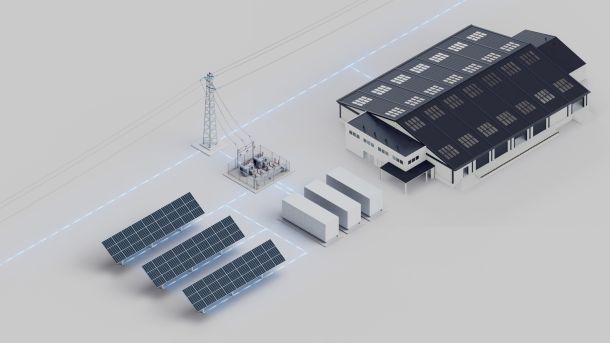

Role of Smart Grids in DER Optimization

Smart grids provide the digital backbone for coordinating solar PV, battery storage, EV charging and flexible loads. Rather than treating these as disturbances, modern grids treat DERs as controllable resources. This requires synchronized dispatch, real-time data exchange and predictive analytics all of which smart grid platforms support.

Interoperability with Solar, Storage and EV Infrastructure

Seamless DER integration depends on interoperability standards and open communication protocols. Smart grids that support IEEE 2030.5, OpenADR and OCPP can interface with a diverse ecosystem of technologies, ensuring that each asset responds to system-wide signals while preserving local priorities.

Enhancing Grid Resilience and Operational Efficiency

Outage Detection and Self-Healing Mechanisms

Self-healing grids detect, isolate and reroute power around faults in seconds. These capabilities hinge on high-speed data transfer, edge decision-making and redundant pathways. Utilities deploying these technologies have seen double-digit improvements in System Average Interruption Duration Index (SAIDI) metrics.

Load Forecasting and Peak Demand Management

Smart grids enable near-term load forecasting using AI models trained on historical and real-time data. This allows grid operators to preemptively flatten peaks, activate demand response programs and reduce reliance on expensive peaking plants all while maintaining reliability thresholds.

Data-Driven Decision Making and Market Participation

Using Analytics for Load Shifting and Tariff Response

With access to granular data, energy managers can identify flexible loads and shift consumption to align with off-peak tariffs or renewable generation windows. Machine learning models can forecast price movements and recommend optimal load schedules, enhancing both cost savings and grid balance.

Enabling Participation in Capacity and Ancillary Services Markets

Smart grids create the infrastructure needed for DERs to bid into wholesale markets. Whether providing spinning reserve, frequency regulation, or reactive power, distributed assets become revenue-generating participants rather than passive endpoints. Regulatory frameworks in regions like CAISO and PJM already reflect this shift.

Regulatory, Economic and Security Considerations

Cybersecurity Challenges in Smart Grid Deployments

As grids become more connected, the threat surface expands. Protecting operational technology (OT) systems from intrusion requires multi-layered security from device authentication to end-to-end encryption. Incidents like the 2015 Ukraine blackout underscore the need for embedded security in grid architecture.

Regulatory Incentives and Investment Signals

Governments are playing a critical role in accelerating smart grid adoption. Policies offering performance-based incentives, grid modernization funds and time-of-use pricing pilots are shaping investment decisions. At the same time, clarity around interoperability standards and market participation rights is becoming a strategic differentiator for technology providers.