As distributed energy systems scale up and interconnect, they introduce new cybersecurity risks that traditional grid protection models were never designed to handle. From solar inverters and battery controllers to DERMS and SCADA platforms, each layer of the digital infrastructure becomes a potential entry point for cyber threats. The result is a fragmented and highly exposed architecture that requires purpose-built defense strategies. Energy operators can no longer treat cybersecurity as a compliance box to tick. It must become a core pillar of design, operation and system resilience.

Why Distributed Energy Resources Are Prime Cyber Targets

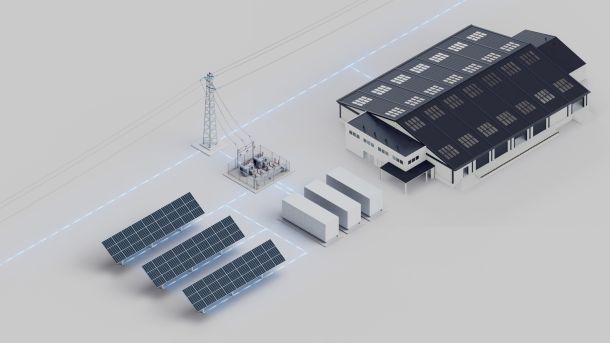

Increased Attack Surface in Modern Grid Architectures

Unlike centralized plants, distributed systems introduce countless points of interaction with the grid. Each inverter, weather station, battery or remote controller that connects over public or private networks widens the potential attack surface. These components often use lightweight embedded software with limited onboard security. Moreover, they are rarely isolated by strong network segmentation, making lateral movement within the system easier once an initial breach occurs.

Examples of High-Impact Cyber Incidents in Energy Sector

The 2015 attack on Ukraine’s power grid demonstrated how malware targeting control systems could trigger physical consequences. The Colonial Pipeline ransomware incident in 2021, while affecting fuel supply, reminded the industry how IT breaches could ripple into critical infrastructure. Similar risks now extend into the DER space, where vulnerable APIs, outdated firmware or exposed remote access protocols can leave facilities open to manipulation or disruption.

Key Vulnerabilities Across DER Infrastructure

SCADA, BMS and Inverter-Level Risks

Many industrial-grade DER components still rely on legacy SCADA protocols that lack encryption or authentication. Inverter firmware may be upgradable over unprotected channels and battery systems often share telemetry over open ports. If compromised, these nodes can be used not just to manipulate energy production but to destabilize grid behavior through coordinated actions.

Communication Protocol and API Exploits

Protocols like Modbus or DNP3 were designed for reliability, not security. Without wrappers like TLS or VPN tunneling, they expose control functions to tampering. Similarly, REST APIs offered by DERMS platforms or asset gateways often lack proper rate limiting, authentication or audit logging, making brute-force or injection attacks viable.

Threats Arising from Cloud Integration and Remote Access

Remote connectivity brings convenience, but also risk. VPNs with weak credentials, shared access tokens or unmonitored cloud platforms can serve as attack vectors. Misconfigured cloud storage or dashboards open to the internet can leak sensitive site data or control interfaces. In many deployments, remote access solutions are bolted on late in the project lifecycle, bypassing the secure-by-design principle entirely.

Zero Trust Architecture for Energy Networks

The traditional assumption of internal network safety is obsolete. In Zero Trust architecture, no device or user is implicitly trusted. Every interaction must be authenticated, authorized and continuously validated. For DER operators, this means segmenting networks by function, limiting east-west traffic and enforcing strict identity-based access policies across SCADA, EMS and field gateways.

Secure-by-Design for DERMS and Edge Devices

Security must be embedded from the first line of code to the last firmware deployment. DERMS vendors should implement role-based access, encrypted data handling and automated patching. Field devices must use signed firmware, physical tamper resistance and secure boot processes. Any system update or remote control function should require multi-factor verification.

Real-Time Intrusion Detection and Response in EMS Platforms

Modern EMS systems should go beyond static firewall rules. By analyzing real-time data flows and comparing them to physics-based models, operators can detect deviations that suggest manipulation or compromise. These models allow the system to flag unexpected power curves, abnormal inverter behavior or mismatched telemetry as signs of a cyber breach, not just equipment failure.

Regulatory Landscape and Compliance Challenges

NIST, IEC 62443 and Sector-Specific Standards

Global frameworks like NIST CSF and IEC 62443 provide baseline guidance, but distributed systems often require tailored implementation. These standards emphasize layered security, asset inventory, risk assessment and continuous improvement. However, compliance alone does not guarantee resilience. Operators must go further by customizing controls for hybrid topologies and edge-heavy deployments.

Operationalizing Cybersecurity in DER Projects

Building Cross-Functional Cyber-Response Teams

Effective response requires coordination between IT security, OT engineering and operations. Too often, security events in DER plants are delayed due to unclear responsibilities. By establishing joint response protocols, conducting regular simulation exercises and appointing cyber leads within OT teams, operators can reduce detection-to-response time and improve containment.

Ongoing Monitoring, Logging and Threat Intelligence

Cyber defense does not end at deployment. Facilities should maintain continuous telemetry logging, centralized event analysis and automated alerting systems. Integrating threat intelligence feeds that cover ICS-specific vulnerabilities can help identify zero-day threats or industry-wide campaigns. Where possible, anomaly detection models should correlate field behavior with historical baselines, creating adaptive thresholds that evolve with system changes.

Cybersecurity ROI: Downtime Avoidance and Asset Protection

Cyber investments often compete with hardware upgrades, but their financial impact is measurable. A single hour of downtime at a large solar or wind site can cost tens of thousands in lost revenue and regulatory penalties. Moreover, attacks that compromise metering data or inverter setpoints can lead to long-term losses through imbalanced grid participation or reduced dispatch eligibility. Securing operations ensures continuity, protects revenue streams and enhances trust among stakeholders.